ML demystified - a high level overview

September 10, 2018 machine learning programming

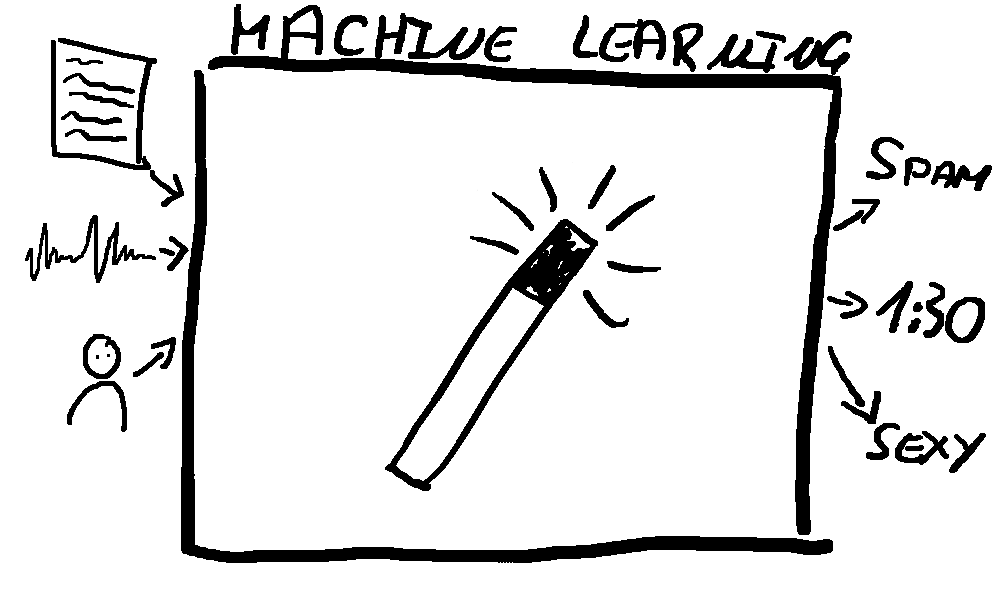

Machine learning is magic to a lot of people. It’s a black box that takes something real and gives us some prediction or analysis that seem way too accurate sometimes. Even if you know for example how a neural network works you might not be sure how a complete machine learning system works.

I will give you an understanding of how you get from the real world thing (like an e-mail, an audio file or a person) to the prediction (“this mail is spam”, “A fork falls on the floor at timestamp 1:30”, “this person is sexy”) without going into any mathematics or coding and using (mainly) plain english.

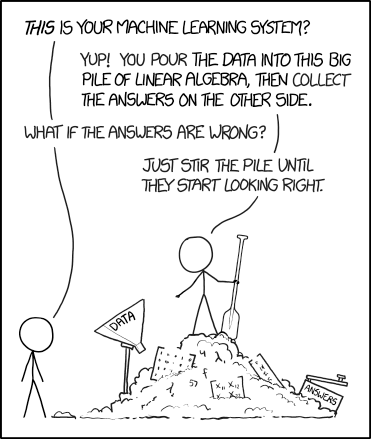

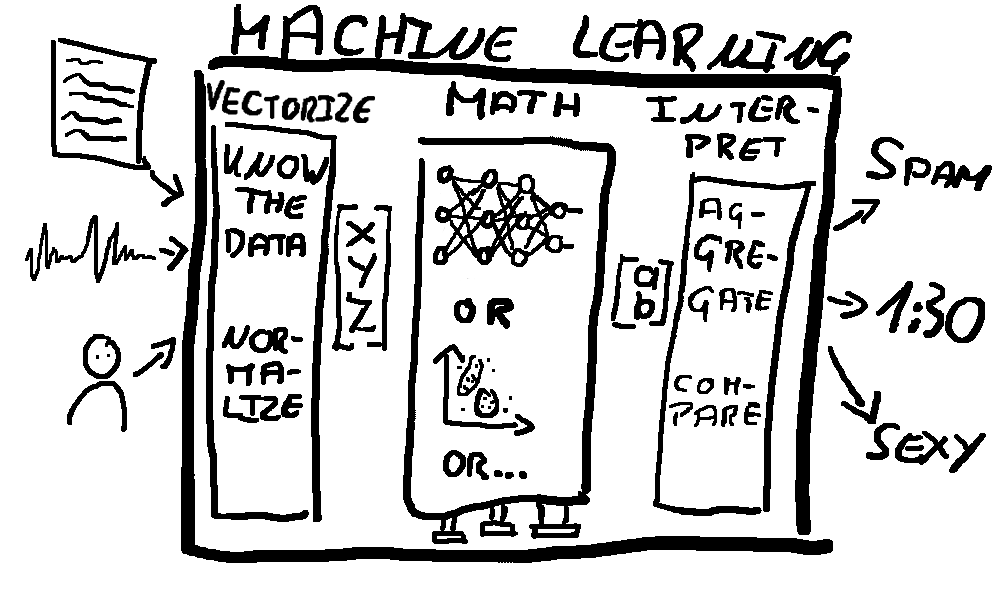

Let’s start out with a comic

And there is a truth to it. At the core of most ML systems there is some

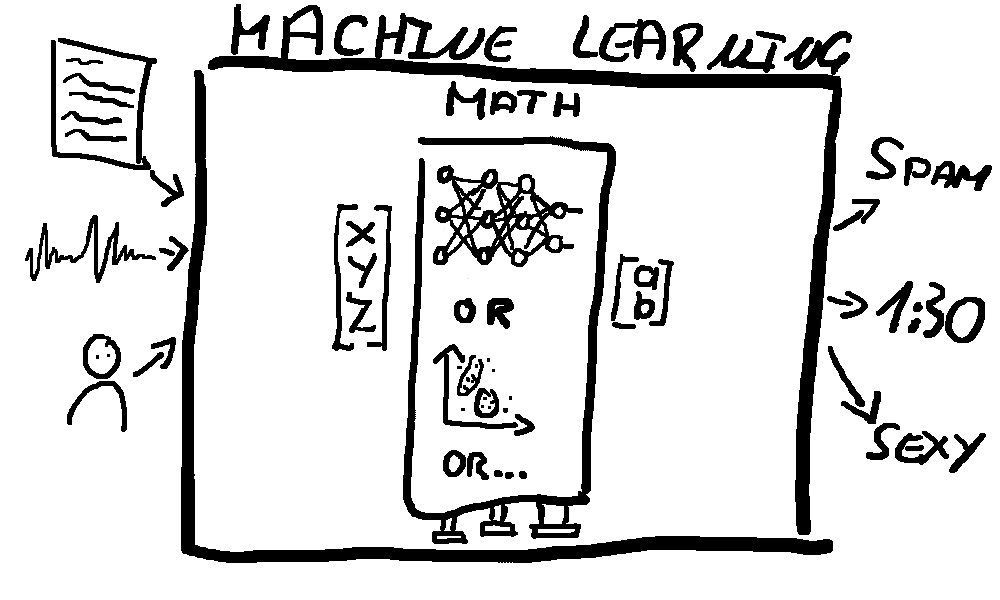

Mathematical System

Neural networks are probably the most widely known but this may be something completely different like a gaussian mixture model. I’m not going to explain these since there are many of them and you should look up resources on the ones that interest you.

We only care about what these systems have in common: Math. They take “math” as input and they output “math”. Usually this means vectors (which is practically a list of numbers).

Since these mathematical systems are domain-agnostic you’ll probably not implement those yourself but rather use a library. What you will do however is tweak it. For example in neural networks you’ll change the number and composition of layers. Maybe 2 is enough or maybe 3 is better. This can often only be explored through trial and error - so best to automate it. Let the system run with multiple different configurations and select the best (that’s part of what the “stir the pile until it starts looking right” line in the comic refers to).

When people talk about training a system this is the part that needs to be trained (just fyi some systems don’t need to be trained). How does the math system output the correct value? Because you trained it. You put in some data, it outputs a (probably wrong) result. You then compare the actual output to what should have been the output and change the math inside the system a tiny bit to make the output a little bit closer to what it should have been. Do this thousands of times with good trainings data and you trained your system.

This of course requires you to have thousands of data entries and their expected output. To train a spam filter you’d need a lot of e-mails of which you know whether they are spam or not. How do you know if an e-mail is spam? Because a real person looked at it and decided if it’s spam. This is called (manual) labeling. If your training data or labels are bad your system will be bad.

Vectors

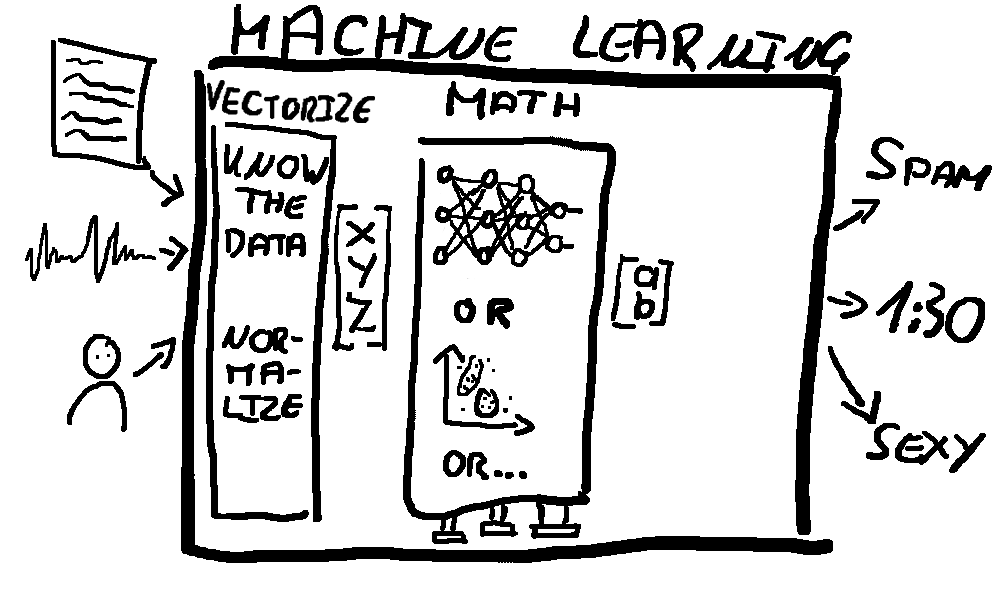

So now we need something that takes our real world thing and transforms it to a vector - this is often called a feature vector since we pick some features to represent the real world thing.

What features should we pick from our real world person? Let’s say we want to make a system that predicts whether a person is sexy or not. For this we could represent the person with 3 features: height, body fat and age.

[180, 20, 946.080.000.000]

Height in cm, body fat in percentage and age in… milliseconds.

This vector is probably going to produce terrible results since the number for age is so much bigger than the other two. Most math systems will be dominated by the giant age number and the other two numbers will have hardly any impact. What we have to do here is normalize the data. In this case normalizing will be simple: Use age in years instead of ms. But maybe we need to normalize more. Maybe body fat changes its importance the older a person becomes? Maybe instead of body fat we should use something like

body fat * 100 / age

or

body fat * (30 - age)^2

Who knows? I don’t because I’m not an expert in knowing who’s sexy.

Maybe height and age are the completely wrong features and will never deliver good results. Maybe what makes a person sexy is their income and the amount of pinky rings they wear.

Now imagine the data you work with is not a person but complex financial records or raw output of audio sensors. To choose good features and normalize them you need a deep understanding of where the data comes from and what it means. Turning the real world into vectors is a crucial task in a ML system since a bad input vector will always return bad results.

For some domains (like audio) there are proven ways to vectorize data but most likely you’ll be building a system specific to your domain and you’ll have to define the feature vector yourself. How do you represent non-numeric features? A boolean could easily be converted to a 0 or 1. What if the country is a feature? You could just number the countries, so America is first, Germany second and so on. Maybe your data is more complicated and you have to get creative. Generating a good feature vector usually involves lots of trials and tests since you’ll have to run the system to know if your vector is any good (“stir the pile until it starts looking right”).

Sometimes this step contains machine learning as well. So you have an entire (or even multiple) ML systems that are only used to generate the input for another ML system.

Output

All that’s left is to interpret the output of our math system. Depending on how the math system is designed this might be a trivial step. Maybe the output is a number between 0 and 1 and indicates a probability. Or it returns a vector [a, b, c, d] where every number is a score for a different possible prediction.

When analyzing audio data you might have created a separate feature vector and output for every 25ms window of a 5 minute long clip - then this step would contain aggregating these results to something simple like “from 1:30 to 1:56 a person is talking”. Or maybe your system compares 2 things then you need to interpret the 2 output vectors relative to each other to come to a conclusion.

So what kind of work might I be doing when I decide to work with ML?

Fucking around with (trainings) data

Most machine learning systems require training. Let’s say you want a system that takes audio files as input and outputs when in the audio clip a fork falls on the floor. Well now you need trainings data. So you need a whole bunch of clips (preferable multiple hundreds or thousands) where forks fall on the floor. And if all your trainings data only contains metal forks falling on marble floors your system will probably not recognize a metal fork falling on concrete. So you need very diverse trainings data. Different forks, different floors, different mics, different background noises, … Good luck finding data for more obscure domains.

Even if you have trainings data it still needs to be labeled - meaning you also need a file that tells you when in each clip the fork is dropped.

Best case scenario: You find fully labeled trainings that fits your use case online.

Worst case scenario: You have to listen to thousands of hours of audio and manually write down every time a fork drops.

Often it’s somewhere in between. You have some labels but not exactly what you need so you need to transform them. Or you have a source (like a SQL database) and can extract trainings data & labels from there.

A more experienced college of mine says he spends around 50% of his time working with (trainings) data (finding, generating, transforming, labeling, …).

Developing a proper vector

Like I said previously: A bad vector will always return a bad result.

You need to decided which data is useful and this might not always be obvious. You’re trying to figure out if a purchase in your web store is fraudulent. What’s important? Geo-location of the buyer, the browser agent or the payment method? Maybe you realize the time of purchase is important. But in your database only your local time is saved. What you really need is the local time in the timezone it was purchased in. So now you have to start normalizing…

One of the examples my professor gave us for normalization:

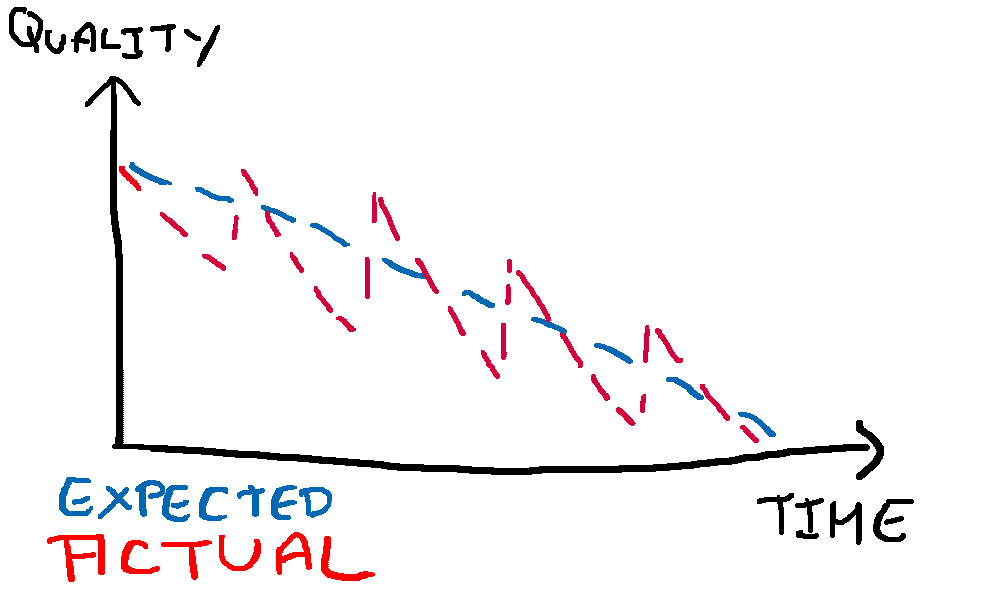

They were trying to predict when a underwater camera would need to be replaced. They had some metrics including the quality of the camera recordings but they didn’t get satisfying results. So they started to look more closely at the measured quality. They expected the quality to slowly decline but it actually looked more like this:

As it turns out the lenses get covered in alga and every month somebody dives down there to clean them and the quality of the recordings spikes. So now they have to normalize their data to reflect the blue line (since the goal is to measure the actual quality of the camera - regardless of whether or not it has been cleaned recently).

That’s a tough one to catch if you don’t know how the data is recorded and that there is somebody cleaning the cameras. Even then: The data is usually just numbers. You have to explicitly analyze or visualize it to see that the quality doesn’t degrade as you expect.

Run experiments

stir the pile until it starts looking right

One of the most asked question in the machine learning lecture was “How do I know how many layers my neural network should have”. A experienced ML expert may hazard a guess based on what worked previously but in the end you’ll just have to try. Our simple “Is this person sexy” system with a 1x3 Vector will probably not need 10 layers. But an image analysis might. Try to find somebody who solved a similar problem and use this as a starting point. Then automate and run many tests.

You might not even know what kind of math system you need. Is a neural network really the best system for your use case? Try to find some publications or papers to figure out what might work. Or try different systems yourself.

Same with the vector. You’ll probably have to run a bunch of experiments to figure out which data is useful.

Actually implement the math part

Maybe your company has very specific requirements, maybe there’s no library available for your specific system / programing language or it needs to be optimized for specific hardware. This is very different work from the rest so make sure you know what you’re in for when you accept a ML position.

Conclusion

A machine learning system needs to turn real world things and data into feature vectors that can then be worked with by whatever mathematical system you choose. Then you need to turn the mathematical output back into a real world prediction. You’ll handle lots of data (especially when training) and you’ll run lot’s of tests and experiments (especially when there are no similar systems as references). Be sure to talk with your potential employer about what work you will actually be doing.